For more than two centuries, amendments have allowed our Constitution to grow with the country. The 13th Amendment, for instance put an end to slavery, while the 19th gave women the vote. It was intended to be amended.

But you have to go back more than 50 years to find a meaningful change to the Constitution. Asked how long we can work as a country without updating the Constitution, Jeffrey Rosen, president and CEO of the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, replied, “The real fear that the founders had was that we would stop listening to each other. They thought self-government was hard, and that crucially requires deliberation and debate.”

Before anyone could even consider a national constitution, of course, there was the Declaration of Independence, ratified in 1776, and the Articles of Confederation, agreed to in 1777, a full decade before the new Constitutional Convention.

Historian Jill Lepore’s latest book, “We the People,” describes a Constitution ratified by the people it governed, and designed to be changed by the very same. In other words, we aren’t stuck with any of it. But at the outset, she said, “The support for the Constitution and its ratification was pretty slender.”

Liveright

In addition to the three equal branches of government and a schedule of regular elections, the U.S. Constitution includes a mechanism for changing the Constitution itself. “They came up with this Article V of the Constitution, which is the amendment provision, which had been insisted on by the people,” said Lepore. “People are like, if we’re going to have a written document, we need to have the ability to amend it ourselves.”

In fact, Lepore says, though we often think of the Constitution as the final draft, it was always designed to be a work in progress. The founding fathers expected it to be revised constantly. “Yeah, they absolutely did,” Lepore said. “And remember, like, a whole bunch of them refused to sign it, ’cause they didn’t think it was good enough.”

Before the states would agree to ratify it, she says, some insisted on revisions; there were more than 200 amendments proposed by the states. The result: a set of amendments, whittled down to ten, that we now know as the Bill of Rights. Ratified in 1791, they include some of the bedrock ideas of modern America: freedom of speech; freedom of religion; a right to bear arms; and, for the accused, the promise of a fair trial.

But the Constitution was also a tangle of compromises, none more tragic than the compromise over the institution of slavery and the exclusion of women from political life.

Rosen says there was one concession, though, that James Madison, one of the document’s framers, would not make. “He refused to admit into the Constitution an endorsement of slavery,” Rosen said. “He said the idea that there could be property in men wouldn’t be written into the Constitution, ’cause they wanted to leave it up to future generations to eradicate slavery.”

Though it took 100 years and a civil war, America at last had what some call its “second founding,” with the addition of amendments that, among other things, abolished slavery, guaranteed citizenship to the formerly enslaved, and gave all men the right to vote regardless of race – trying to make the promise of the Declaration of Independence (which was absent from the Constitution) real.

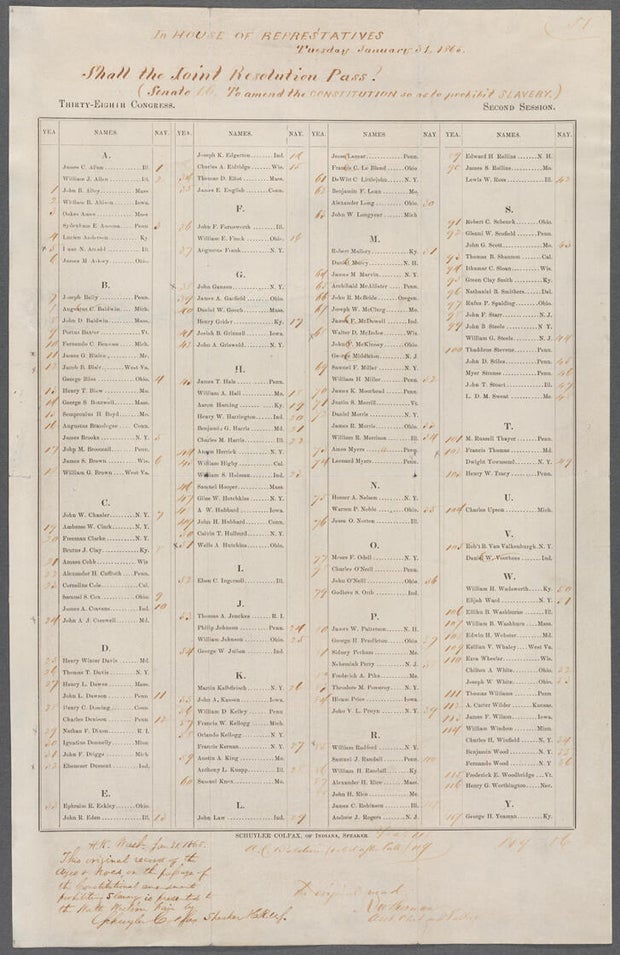

New York Public Library

“It was just this incredible day,” Lepore said, of when the House voted on the amendment abolishing slavery. “The galleries were packed. They even had women in the galleries. Frederick Douglass’ son, Charles Remond, was in the gallery. And the House just was nearly blown over by the burst of energy.”

These days, even though the language of the Constitution hasn’t changed lately, the interpretations still have, with the Supreme Court regularly reinterpreting our nation’s founding framework. But Rosen noted, “None of the founders expected constitutional change to come mostly from the Supreme Court.”

In fact, the Constitution does not give the Supreme Court the right to determine the constitutionality of a law passed by Congress; they just assert the right to do so.

Rosen says the Constitution is still the answer to our problems, not the cause, and yet, for the moment, he worries about how it’s being used.

Simon & Schuster

“There’s a broad agreement that checks-and-balances are not working now the way they were supposed to,” he said. “Congress has stopped acting and refuses to check presidents of its own parties. And the courts have become vastly more powerful than the founders anticipated in deciding almost every political question, and insisting that they have the last word.

“So, whether or not you like what’s going on in our politics today, I think you have to say this is not what the founders intended,” Rosen said.

The founders never claimed to have created a perfect country. But in the Constitution, they did try to pass on the tools to build a “more perfect union.”

To people who say the Constitution may have no bearing on life today, Rosen said, “The Constitution was written in the 18th century, but it was expressing principles vindicated as recently as yesterday’s news. The basic idea that a president should not be a king, that power corrupts, that we are a government of laws – these are the ancient ideas of freedom. And every country that has forgotten them has descended into dictatorship and tyranny. It is historically irresponsible to dismiss the Constitution as outdated. It’s absolutely eternal and timeless.”

READ AN EXCERPT: “We the People: A History of the U.S. Constitution” by Jill Lepore

For more info:

- The United States Constitution (Full text)

- “We the People: A History of the U.S. Constitution” by Jill Lepore (Liveright), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available September 16 via Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Bookshop.org

- Jill Lepore, The New Yorker

- “The Pursuit of Liberty: How Hamilton vs. Jefferson Ignited the Lasting Battle Over Power in America” by Jeffrey Rosen (Simon & Schuster), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available Oct. 21 via Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Bookshop.org

- Jeffrey Rosen, president and CEO, National Constitution Center

- “Celebrating 250 Years of the United States at NYPL,” New York Public Library

Story produced by Mary Raffalli. Editor: George Pozderec.

0 Comments